Physician-scientist Piro Lito

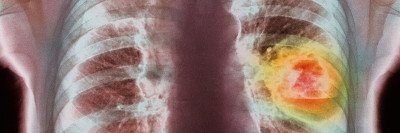

Among cancer biologists, finding a drug that can target KRAS proteins has been considered the Holy Grail.

KRAS is one of the most commonly mutated proteins in cancer but until recently was thought to be essentially undruggable — its nearly spherical shape makes it a slippery target. But in the last few years, scientists have found ways to block the action of one particular version of mutated KRAS, called KRAS G12C. The protein cycles between an “on” and “off” form, creating subtle shape changes that enable drugs called KRAS G12C inhibitors to bind to and disable it. These drugs, which are now in phase I clinical testing, have shown great promise for people with lung cancer, but their benefits are partial: Tumors shrink incompletely and in only a subset of patients.

A new study from scientists at Memorial Sloan Kettering, published online on January 8 in Nature, has identified a mechanism for this pattern of response — and suggests ways to circumvent it.

According to Piro Lito, a physician-scientist in the Human Oncology and Pathogenesis Program and the corresponding author on the paper, treating cancer cells growing in a dish with these inhibitors causes cells to produce new KRAS G12C protein. Some of the newly synthesized protein takes on a shape that is insensitive to the drug, which in turn enables some cells within the population to escape its effects. By comparison, cells in which the new protein remains in a drug-sensitive state continue to be inhibited by the treatment.

Dr. Lito and his colleagues found that this adaptive response can be minimized by adding a second drug that helps keep the new KRAS G12C protein in the druggable state. Clinical trials of such combinations are set to begin in early 2020.

From the Lab to Clinic in Record Time

MSK has played a key role both in the preclinical and early clinical development of KRAS G12C inhibitors. In a 2016 paper published in Science, Dr. Lito and his colleagues described the mechanism of action by which KRAS G12C inhibitors inactivate the mutant protein. From there, it was a quick journey to the clinic.

“These drugs target only mutant KRAS G12C and spare wild-type KRAS,” says Yulei Zhao, a postdoctoral fellow in the Lito lab and a co-first author on the new paper. “For that reason, they are likely to have minimal toxicity.”

The study’s novel findings were enabled, in part, by a technique called single-cell RNA sequencing, which allowed the researchers to measure the drug responses of thousands of individual cells simultaneously. From these data, they were able to determine that some cells remained inhibited by the drug, whereas others rapidly adapted to treatment; this was crucial to determining the mechanism of adaptation.

“If we had used bulk analysis approaches, we would have seen only the average effect of treatment across the population,” says Jenny Xue, a Tri-I MD/PhD student in the Lito lab and the paper’s other first author. “The complexity of this adaptive process at the level of individual cells would have been masked.”

Immediate Clinical Implications

A number of KRAS G12C inhibitor trials are now accruing patients at MSK. These trials are led by Gregory Riely in the Thoracic Oncology Service and Bob Li in the Early Drug Development Service, in collaboration with Dr. Lito.

“Our study helps us better understand how cancer cells adapt and tolerate treatment and in identifying combinations therapies that can improve outcomes in patients,” Dr. Lito says.