When Memorial Sloan Kettering cell biologist Richard White goes fishing, he stays in the lab. His catch is small — just a few centimeters long — but the payoff is huge.

Dr. White is using the unassuming zebrafish as a model system for understanding cancer. The aquatic specimens have several virtues that make them ideal for this purpose. For one, they’re transparent — you can see right through their scales to the cancers forming underneath. They’re also cheap and easy to genetically engineer. And they get cancer naturally in the wild; researchers believe the basic mechanisms are similar to those in humans.

How the Richard White Lab Studies Zebrafish to Understand Cancer

“In fish, you can study developmental and genetic changes in the context of the whole animal on a huge scale, and you can really watch how cancer develops,” says Dr. White.

In a new study published today in the journal Science and featured in the New York Times, a team of researchers including Dr. White used zebrafish to shed light on a fundamental question that has long puzzled cancer biologists: Why doesn’t every cell with mutated genes develop into cancer?

Turning Back the Clock

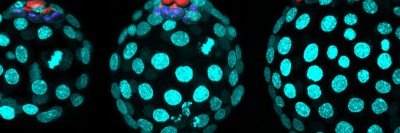

Though fish with mutations in two cancer genes called BRAF and p53 are guaranteed to get cancer, not every cell in the fish’s body turns cancerous. Those that do all express a protein called crestin, which is normally active only during embryonic development, suggesting that somehow these cells have been turned back to a more embryonic state.

The new study used a fluorescently labeled version of crestin to follow the first cells that head down the path to tumor formation. Due to the see-through nature of the fish, the researchers were able to watch the process in real time, without having to kill the fish to see the cells in action.

The paper marks the first time that researchers have been able to observe cancer in a live animal from the birthplace of a single cell. And it suggests that treatments that block crestin activity might prevent mutated cells from turning into cancer.

“The zebrafish is rapidly expanding as a way to study cancer,” Dr. White says. “It complements what can be done in other systems like cell cultures and mouse models but gives us tremendous flexibility in terms of what we can study. We see these fish as one of the next big things in cancer.”

Model for Metastasis

Dr. White is also using zebrafish models to study metastasis, the process whereby cancer cells spread from one site in the body to another. For that purpose, he developed a stripeless strain of zebrafish that makes it even easier to see where the cells go. He named the fish Casper, after the cartoon ghost.

Although metastasis is responsible for the majority of cancer deaths, we know very little about how it happens or how to prevent it. “As an oncologist I found it incredible that survival rates from metastatic cancer are essentially unchanged since the 1960s,” says Dr. White. Frustrated by the slow rate of progress, he adopted an innovative approach to the problem of metastasis using his ghostlike fish and evolutionary biology methods that consider the role of driver mutations.

Casper provides the MSK team with a rapid visual readout of metastasis and allows them to probe the complex interplay of genes at work in the tumor cells and in the noncancerous tissues they invade.

“There may be a hundred different ways for a tumor to metastasize,” he explains. “Rather than looking at the multitude of individual genes responsible, we are asking, ‘What are the underlying processes that drive the tumor cells to do this?’”