Johanna Joyce, who heads a laboratory in the Sloan Kettering Institute’s Cancer Biology and Genetics Program

Most cancer deaths occur when the disease spreads, or metastasizes, from the original tumor site to a distant location. In breast cancer patients, metastasis to the brain can occur months or years after seemingly successful treatment of the primary tumor.

Now Memorial Sloan Kettering researchers have found that a protein called cathepsin S may play a key role in the spread of breast cancer to the brain. A complex interplay between breast cancer cells and certain surrounding cells called macrophages induces both cell types to secrete increased levels of cathepsin S, an enzyme that promotes the cancer cells’ ability to metastasize.

In addition to potentially helping doctors predict which breast cancer patients are at increased risk for brain metastasis, the discovery, published recently in Nature Cell Biology, suggests that cathepsin S could be an important target for new drugs.

“Brain metastasis is a devastating development of breast cancer, and the current therapeutic options are limited,” says cancer biologist Johanna Joyce, who heads a laboratory in the Sloan Kettering Institute’s Cancer Biology and Genetics Program and led the study. “To have an increased understanding of the process but also a target that we can think about going after is exciting.”

Interplay Both Home and Away

In order to take root and grow, metastatic cancer cells must find ways to exist in a potentially less nurturing, even hostile, setting. Researchers have known that cancer cells rely partly on their microenvironment — the noncancerous cells, molecules, and blood vessels that surround a tumor — in order to survive and grow. But much less has been known about how the microenvironment may confer upon cancer cells the capacity to metastasize. Dr. Joyce and first author Lisa Sevenich, a member of Dr. Joyce’s laboratory, were also interested in how these noncancerous cells at metastatic sites react when they encounter the tumor cells. To investigate these questions, the research team studied mice implanted with human breast cancer cell lines that are known to spread to the brain, bone, and lung. They looked at how both the tumor and its surrounding microenvironment change during metastatic progression.

Robert Bowman and Lisa Sevenich, coauthors of the study and members of Dr. Joyce’s laboratory

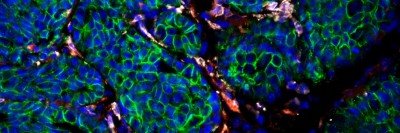

The cancer cells and surrounding cells were subjected to genetic analysis to see which genes were more active than normal. In mice with brain metastases, the cathepsin S gene was significantly overexpressed. Interestingly, the tumor cells produced more cathepsin S at the beginning of metastasis and then tapered production, in parallel with a progressive increase in macrophage cathepsin S levels within the brain.

The reciprocal relationship suggests that breast cancer cells become equipped for metastasis through the two-way signaling between tumor cells and macrophages in the microenvironment. The interplay between the two cell types takes place both at the primary tumor location and at the metastatic site in the brain.

“The increase in cathepsin S expression occurs in a subset of cells in the primary tumor, and we infer that those are tumor cells that go on to seed brain metastases,” Dr. Joyce says. “But the increase is really most pronounced at the metastatic site in the brain. We view it as bidirectional education over the course of metastasis between both components of the tumor — the cancer cells and the cells in the microenvironment are each changing in response to signals from the other.”

The researchers showed that cathepsin S enables the cancer cells to penetrate through the blood-brain barrier, a densely packed vascular structure that protects the brain from most large molecules in the blood. Cathepsin S is a protease, a type of enzyme that degrades proteins. The researchers found that cathepsin S cleaves a protein called (JAM)-B, which normally helps hold cells in the blood-brain barrier together. The higher levels of cathepsin S presumably negate (JAM)-B’s effect and allow the cancer cells to penetrate the barrier.

Blocking Cathepsin S to Stop Metastasis

To validate the role of cathepsin S in promoting brain metastases, the researchers inhibited it with experimental drugs. This significantly reduced the development of brain metastasis in the animals. To be effective, the drugs needed to block cathepsin S in both the cancer cells and the macrophages. Dr. Joyce says that although related cathepsin S inhibitors are already in clinical trials for autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, “they are not currently being tested in cancers. We hope that may change soon.”

In addition, she says she is intrigued that genes for proteases besides cathepsin S are expressed at higher-than-normal levels in the tumor and microenvironment cells they analyzed. “I’m really interested in whether these other proteases might play complementary roles in helping brain metastases grow after cathepsin S has allowed them to take the critical step of entering the brain,” she says.