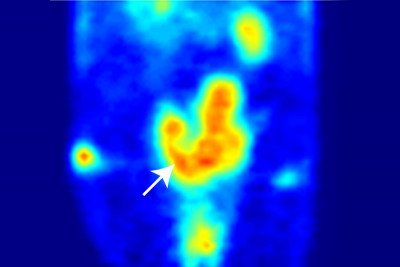

This PET scan shows the pelvic region of a mouse with a prostate tumor (arrow). The red areas represent regions of high transferrin uptake.

A Memorial Sloan Kettering research team is developing a medical imaging agent that could result in better ways to detect prostate cancer and monitor a man’s risk of developing a life-threatening form of the disease.

Working in mice, the investigators used PET scans to track transferrin, a protein that normally is present in the bloodstream and can bind to fast-growing cells such as tumor cells. Their findings suggest that this strategy could be used to measure a biological process that is known to be highly active in some tumors, causing the onset of an aggressive form of prostate cancer. The researchers also found that transferrin PET scans might allow the disease to be detected early, before any tumor growth can be seen by conventional imaging techniques.

“If we can develop it for use in patients, this technology could have a broad impact on prostate cancer diagnosis and treatment monitoring,” says Jason Lewis, Vice Chair for Research in the Department of Radiology. He led the study, which was published in Nature Medicine in October, together with physician-scientist Charles L. Sawyers, Chair of the Human Oncology and Pathogenesis Program.

A New Imaging Agent

PET scans are sensitive imaging tests that can give detailed information about how tumors or body organs function. These scans produce three-dimensional images by tracking the location of a molecule that has been linked to a radioactive substance called a radionuclide and introduced into the body in low amounts.

Dr. Lewis and his colleagues designed a new PET imaging agent by coupling transferrin — a protein that occurs in the body naturally and plays a role in transporting iron to different tissues—to a radionuclide called zirconium-89.

Transferrin is more abundantly taken up by cancer cells compared to most normal cells and tissues, and has been explored for decades as a potential tool for cancer imaging and therapy. “However, earlier strategies to visualize transferrin uptake often produced images that were very challenging to interpret, mainly because of the properties of the radionuclides previously used,” Dr. Lewis says.

With zirconium, a longer-lived radionuclide, the researchers were able to detect and measure transferrin uptake in mouse models of prostate cancer, producing tumor images of unparalleled quality.

Visualizing a Tumor’s Biology

The study also revealed that transferrin PET scans might offer a new way to noninvasively study the biology of a tumor.

“Prior work has shown that a tumor’s uptake of transferrin can be driven by the activity of MYC, a very important oncogene that commonly is mutated in many types of cancer,” says Michael Evans, a lead author of the study and a postdoctoral research associate in Dr. Sawyers’s lab. (Oncogenes are genes that, when mutated, can promote cancer development.)

In approximately 30 percent of men with prostate cancer, tumors carry mutations in MYC that are known to correlate with poor outcomes. The researchers found that their imaging technique can be used to measure the activity of MYC in tumors, making it possible to distinguish some aggressive tumors from those that are more benign.

In addition, the investigators discovered the method was capable of detecting prostate cancer early, before any evidence of disease can be found using conventional diagnostic tools such as biopsy, MRI scans, or CT scans. “This is most likely due to the fact that we are visualizing an underlying cause rather than a symptom of the disease,” Dr. Evans explains.

Toward the Clinic

Efforts are now under way to develop the imaging agent for use in patients. The investigators note that transferrin PET scans could make it easier to manage prostate cancer in the future — for example, by allowing physicians to predict outcomes and make better-informed treatment decisions for newly diagnosed patients.

In some patients, the disease spreads quickly from the prostate to other organs, but in many others it is slow growing and unlikely to cause serious problems during a man’s lifetime. Dr. Evans says there is an unmet need for better tools to identify which patients need active treatment, so that men with less aggressive forms of prostate cancer can be spared from having therapies or invasive tests they don’t need.

The investigators also hope that transferrin PET could be used to track treatment responses to some new cancer drugs — in particular a new class of therapies that works by inhibiting MYC activity and is currently in patient trials — as well as to predict early which patients are most likely to benefit from such drugs.

“But prostate cancer is not the only disease in which transferrin PET scans might be useful,” Dr. Lewis adds. The investigators are exploring the potential use of the imaging agent in animal models of a number of other cancers, including breast cancer, lymphoma, and glioblastoma brain tumors.