Graduation is an opportunity to gather with classmates for a final time to mark the end of a long and often life-altering experience, and also a moment for family, friends, and mentors to celebrate what these graduates have achieved. At Memorial Sloan Kettering, the list of accomplishments of our young scholars is quite long — and they’re just getting started.

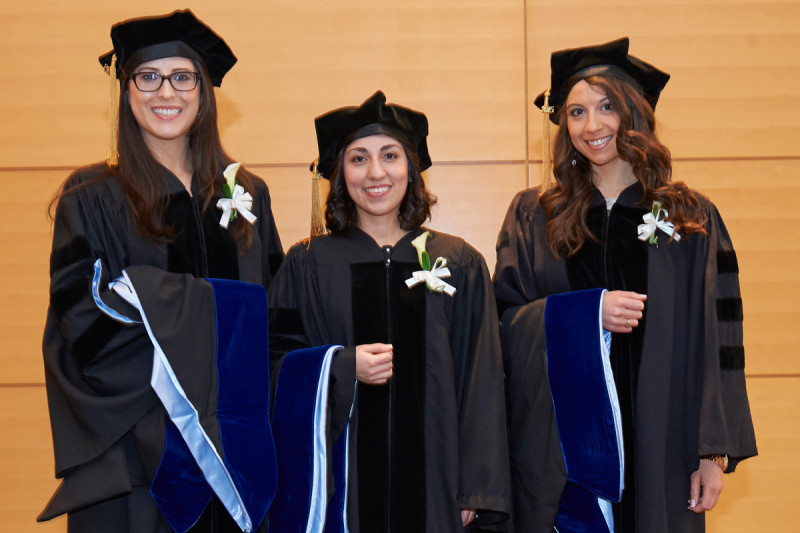

At MSK’s 36th annual Academic Convocation on May 21, President and CEO Craig B. Thompson presided over an afternoon ceremony in which we honored students who conducted their doctoral dissertation work in MSK laboratories though a partnership between Weill Cornell Medical College and the Sloan Kettering Institute. Younger MSK physicians, scientists, and postdoctoral research fellows, as well as established clinicians and investigators from the institution and beyond, were also recognized. In addition, students of the Louis V. Gerstner, Jr. Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences (GSK) received their PhD degrees during the school’s fourth annual Commencement. At this year’s ceremony, three students received degrees, bringing the total number of graduates of the school to 25.

Lessons from a Seasoned Scientist

Robert A. Weinberg, a founding member of the Whitehead Institute at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Daniel K. Ludwig Professor for Cancer Research at MIT, was presented with an honorary doctorate of science degree as well as the Memorial Sloan Kettering Medal for Outstanding Contributions to Biomedical Science. Dr. Weinberg, an internationally recognized authority on the genetic basis of human cancer and a pioneer in cancer research, is most well known for his discovery in the early 1980s of the first cancer-causing gene, the Ras oncogene.

Dr. Weinberg’s Commencement address was an eloquent and personal account of how his own past made him who he is today. His forebears lived in small villages in northwest Germany, “peddling goods, moving from farm to farm, lending money, selling dry goods,” he said. He told the story of his grandfather, who was killed after noticing that his stable boy had left a handful of straw on the floor of a stall housing a horse he intended to sell to a Prussian cavalry officer. As his grandfather reached into the stall to clean up the straw, he was kicked by the horse and died. “I realized that there was a life message in this,” he said. “Perfection is the enemy of the reasonably good, and striving for the absolutely flawless — the perfect experiment — often derails progress of all sorts.”

An “Almost Accidental” Step Leads to a Life in Science

In 1938, his parents escaped Germany and came to the United States. As a young man, Dr. Weinberg did his undergraduate work at MIT “because friends of my parents had sent their sons to MIT. My parents knew little about American higher education, and I didn’t know much more than they did.” It was an “almost accidental” step in his life, he said. After a year of graduate school, also at MIT, Dr. Weinberg took a year’s leave of absence and went to a small college in Alabama to teach biology. The student body numbered 600 African-Americans and two whites.

“On weekends, I’d carry sacks of rice and flour to sharecroppers who lived in small tent settlements, having been evicted from their land for registering to vote,” he recalled. It was a formative experience, and here, too, he learned a lesson: “Teaching is a sacred vocation. It’s the time when you can pay the world back for what others taught you. Like the threat of imminent death, teaching clears the mind, forcing you to think through conceptually complex issues and relate them in simple, accessible ways to students who are eager to learn but who are often put off by pedagogues intent on showing how complex and inaccessible science is — rather than the opposite.”

As his career wound on, Dr. Weinberg spent time at the Weizmann Institute in Israel, the Salk Institute in California, and the MIT Center for Cancer Research. He “stumbled from one research project to the next. … When you apply for grants from the National Institutes of Health, they ask you what you intend to discover. How on earth can anyone know what they’re going to discover? Certainly I never knew, and I still don’t.”

“I went into cancer research because it was so interesting,” Dr. Weinberg concluded. “I confess that to this day when I run into someone who wants to do cancer research because they want to improve the human condition or solve the riddle of the disease that killed their great-aunt, I’m suspicious that they’re doing it for the wrong reasons. For me, the really good cancer researchers do what they do because they find it fascinating, challenging, and all encompassing. Remember, 95 percent of humanity does not enjoy going to work every morning. Make sure you’re different!”

Lessons from a Young Scientist

Jenny Melissa Karo, a member of the 2015 GSK graduating class, shared remarks intended for her classmates. She talked about several key principles she had learned during her time at the school.

On observation: “Successful scientists know how to ask the right questions, but also how to be keen observers and make note of anomalies — to realize that when something crazy happens time and time again, it might be the rule, not the exception. That is the sign of a scientist. … It is that, and the passion for discovery and limitless curiosity, which differentiates a scientist from everyone else.”

On collaboration: “From day one, GSK teaches its students how to work with one another, bouncing ideas off each other. … My project would not have come to fruition if it weren’t for the multidisciplinary scope of the GSK graduate program. It is this focus on collaboration — building bonds between classmates, lab mates, and across departments — that’s necessary for the growth of science in the 21st century.”

On communication: “Together, we must learn how to better communicate our research to each other and to lay audiences. Even between departments, conclusions are lost due to complex vernacular. … It is essential for young scientists to learn how to tell our story effectively.”

On determination: “In 2012, [physician-scientist] Siddhartha Mukherjee, author of The Emperor of All Maladies, spoke on this stage [delivering the Commencement address]. He compared the fervor of a science researcher to a cocaine addict craving their next hit. ‘Don’t forget the addiction,’ he said — and I haven’t. It’s that passion for creating and discovering knowledge — running experiments throughout the night and skipping meals to see the results of your home-run experiment — that epitomizes most individuals in this room.”

On celebration: “Celebrate the wins, even if they’re small. Successful miniprep? Awesome! Finally genotyped the perfect mouse? Amazing! Some of my biggest accomplishments in graduate school were successfully running multiple 96-tube plates on the flow cytometer at … Collective camaraderie, being genuinely excited for one another’s achievements and sharing a drink when times get rough — this is what keeps students and postdocs coming to work with a smile on their faces and determination behind their eyes. Remember, we are all in this together. Basic biological science fueled by many in this audience remains the key to fostering the future innovations that will revolutionize the healthcare industry. Together, we can make a difference and continue to make strides tackling today’s pressing medical ailments.”

MSK Honors Its Own

Among those in the MSK community who were honored at this year’s Convocation was postdoctoral fellow Julian Lange, the recipient of first Tri-Institutional Breakout Prize for Junior Investigators. The prize was established by Cornelia Bargmann of the Rockefeller University, Lewis Cantley of Weill Cornell Medical College, and Charles Sawyers, Chair of MSK’s Human Oncology and Pathogenesis Program. Each of these scientists received a 2013 Breakthrough Prize for Life Sciences and decided to contribute part of their award to help establish what will now be an annual award that recognizes and encourages young scientists at the outset of their careers.

Also honored was Diane Stover, Chief of the Pulmonary Service in the Department of Medicine. Dr. Stover received the Willet F. Whitmore Award for Clinical Excellence. “Dr. Stover is a doctor’s doctor,” said MSK Physician-in-Chief José Baselga in presenting the award. “A colleague has said of her, ‘She is the physician you want to care for your closest loved ones — and yourself.’”