Guardian immune cells called regulatory T cells (Tregs) protect us from dangerous autoimmune reactions, but can blunt the effectiveness of cancer immunotherapies. A protein called Foxo1 (pink) is important to Treg function. (Image courtesy of Nature)

With great power comes great responsibility. Spider-Man wasn’t talking about the immune system when he said this, but he could have been.

Every day, your immune system successfully fends off a battalion of harmful invaders — the many thousands of bacteria, viruses, and other microbes that can cause disease. It also routinely nips cancer in the bud, preventing aberrant cells from turning into deadly tumors.

But like any powerful weapon, the immune system needs to be wielded carefully, to prevent harm to innocent bystanders.

“The immune system is a double-edged sword,” says Memorial Sloan Kettering immunologist Ming Li, who studies the biology of immune cells. “It can benefit the individual if it targets foreign pathogens or cancer. But if it attacks your own tissue, it can be dangerous.”

This is a problem for patients receiving cancer immunotherapy, who sometimes experience serious immune-related side effects — like inflammation in the gut or lungs — as a consequence of unleashing the immune system’s full power.

How to direct the immune system to attack cancer while sparing healthy tissues is the subject of two new papers in the journals Nature and Cell published by Dr. Li and members of his lab.

The papers open up new avenues for controlling immune-related side effects and point the way to safer, more-effective immunotherapy treatments.

Tipping the Balance

Immunologist Ming Li

In the first paper, published in Nature, Dr. Li and colleagues focus on a group of immune cells called regulatory T cells (Tregs, pronounced “T-regs”). These guardian-like cells serve a protective role in the body: By tamping down excessive immune responses, they help prevent autoimmunity — a condition in which the immune system attacks healthy cells.

But these cells can also limit the effectiveness of cancer immunotherapies by prematurely reining in an immune response to cancer. Researchers have shown that the more Tregs found in a patient’s tumor, the worse the prognosis. For that reason, doctors are very interested in selectively eliminating Tregs at the site of tumors while sparing those in normal tissues.

Dr. Li’s team had previously shown that a protein called Foxo1 is important to Treg function in mice. In this study, they found that the Tregs in tumors have lower levels of Foxo1 compared with Tregs in healthy tissues. The lower level of Foxo1 in cancer-associated Tregs suggests these cells will be more sensitive to drugs that target this particular protein.

“This gives us a window to selectively target the Tregs in the tumor rather than those in healthy organs,” says Chong Luo, who is the first author on the paper and a graduate student in the Li lab at the Sloan Kettering Institute. “There is a lot of therapeutic potential in being able to separate the antitumor immune response from autoimmunity.”

Patrolling the Local Neighborhood

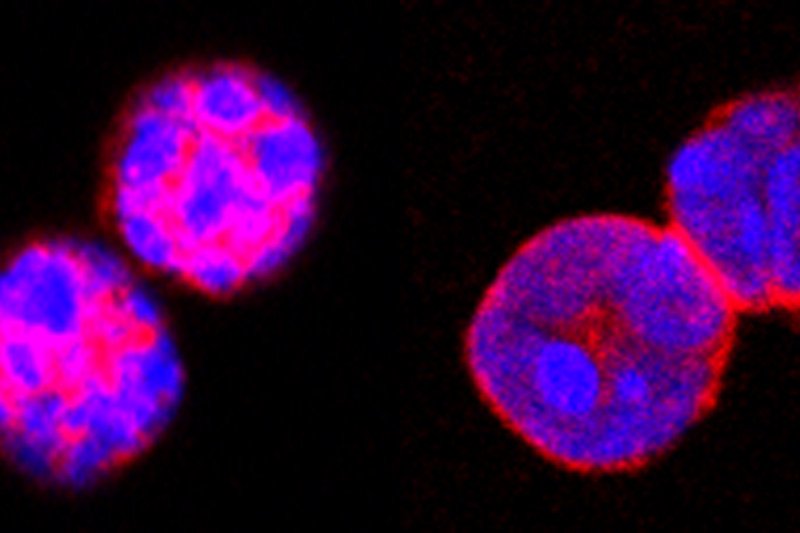

In the second paper, published in Cell, Dr. Li and colleagues identified a previously unknown type of immune cell capable of responding to cancer in its earliest stages.

In studies done in mice, the team uncovered a distinct group of immune cells that leapt into action at the first signs of cancer, helping to quash tumor development.

These cancer “early responders” were different from other previously identified immune cells — such as the lymphocytes that fight bacteria and viruses — in that they don’t travel through the blood and lymph fluid to reach a site of infection. Instead, they are already present in local tissues, as if lying in wait for danger.

“These lymphocytes patrol tissues, respond to early cancerous changes, and help to clear the body of tumor cells,” says Saïda Dadi, the paper’s first author and a postdoctoral fellow in the Li lab.

Identifying a new type of cancer-fighting immune cell is important, explains Dr. Li, since it provides doctors with a potential new target for therapy. “If we want to mobilize all the different ways the immune system can fight cancer, this new class of immune cells provides us with another potential lever.”